Your First Line of Defense When It Matters Most

In high-risk industries like oil and gas, petrochemical and refinery operations, standard valve performance isn’t enough. The true test of a critical safety component comes during an emergency specifically, a fire. A fire safe valve is engineered to perform one essential function during and after exposure to extreme heat: contain the fluid, prevent catastrophic escalation, and help isolate the event.

However, not all valves marketed as “fire safe” are created equal. The difference between marketing claims and proven performance lies in rigorous, standardized testing. For engineers and procurement specialists, understanding API 607 and API 6FA fire-test certifications is not about checking a box; it’s about specifying equipment with proven real-world readiness to protect personnel, assets, and the environment.

What Does "Fire Safe" Really Mean? The Certification Explained

A fire-safe certification is not a design specification but a performance standard. It proves the valve can maintain a seal under defined fire conditions. The key international standards are:

API 607 (and its ISO counterpart, ISO 10497): This is the primary standard for testing quarter-turn valves (like ball and butterfly valves) and other valves with non-metallic seating. It simulates a hydrocarbon pool fire scenario.

API 6FA: This standard is derived from API 6FA is specified for a broader range of valves used in the oil and gas industry. The test protocols are similar but are integrated within the API specification framework.

The core promise of these standards is that a certified valve will:

1. Contain Internal Pressure during the fire.

2. Limit External Leakage to a specified maximum rate through the stem and body seals.

3. Remain Operable (able to be cycled) during or after the event to facilitate emergency isolation.

Inside the Furnace: How Fire Tests are Performed

The certification process is brutal and meticulously controlled, designed to separate truly resilient designs from inadequate ones.

The Standard Test Sequence:

1. Pre-Test Cycle & Seal Check: The valve is cycled and its seat leakage is measured at room temperature to establish a baseline.

2. Fire Exposure: The mounted valve is placed into a furnace and subjected to a flame temperature between 1400°F – 1700°F (760°C – 927°C) for a standard 30-minute duration. The valve is pressurized with a test medium (water or air) during this entire period.

3. Cool Down (Quench): While still pressurized, the valve is sprayed with a deluge of water to simulate emergency fire-fighting efforts and induce thermal shock.

4. Post-Fire Seal Check: After cooling, the valve’s external leakage (through the stem and body) and internal leakage (through the seat) are measured against strict maximum allowable rates.

The Critical Mechanism: Soft Seats vs. Metal Backup

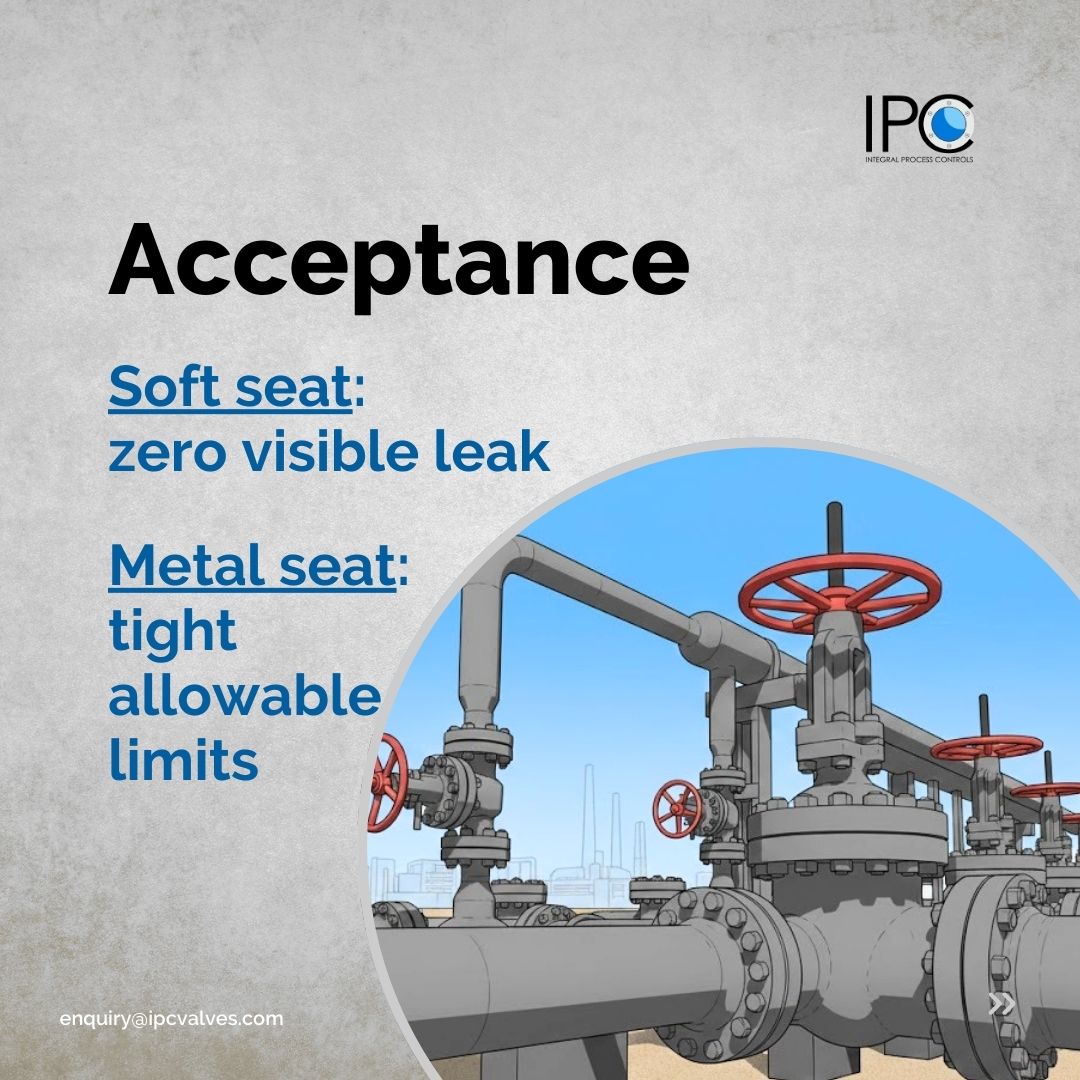

This is the heart of fire-safe design. Most modern valves use polymer soft seats (like PTFE, RPTFE, Nylon) for excellent bubble-tight shutoff at normal temperatures. However, these materials will combust or melt in a fire.

The Solution: A certified fire-safe design incorporates a metal-to-metal backup sealing system. Under normal operation, the soft seat provides the primary seal. When the soft seat is compromised by heat, the valve’s internal geometry forces the metal backup surfaces (e.g., ball against metal seat ring) into contact, creating a secondary seal that maintains containment.

When is Fire-Safe Certification Absolutely Necessary?

Specifying a fire-safe valve is a risk-based decision. It is typically mandated for services involving flammable, toxic, or hazardous fluids where a leak during a fire would significantly increase danger. Key applications include:

- Hydrocarbon processing and transfer lines (crude oil, naphtha, LNG, fuels).

- Chemical plant lines with volatile or toxic substances.

- Jet fuel service at airports and refining.

- Any application where company safety engineering standards or local regulations require it.

A simple rule: If the fluid can feed a fire, the valve protecting it should be fire-certified.

The Buyer's Checklist: Beyond the Certificate

To ensure true compliance and safety, your procurement process must look deeper. Here is a critical documentation checklist:

1. Valid Test Report: Request the actual fire-test certification report from a recognized, independent testing laboratory. The report must be for the exact valve model, size, pressure class, and seat/trim materials you are purchasing.

2. Manufacturer’s Declaration: Obtain a formal Fire-Safe Compliance Declaration from the manufacturer (like IPC), stating the valve’s conformance to API 607/6FA.

3. Design Verification: Confirm the design includes a proven metal backup sealing system. Ask for cutaway diagrams or technical notes explaining the fire-safe mechanism.

4. Material Traceability: For crit

The IPC Commitment to Certified Safety

At IPC, our approach to fire-safe valves is integrated into our core manufacturing philosophy. With over 25 years of experience serving the stringent demands of refinery, power, and chemical sectors, we understand that safety is engineered, not assumed. Our range of fire-tested ball valves and other critical valves are designed with robust metal backup systems and constructed in our 25,000+ sq. ft. facility to meet the highest standards.

We provide not just a product, but the full compliance documentation and technical support you need to specify with confidence, ensuring your systems are prepared for real-world challenges.

Conclusion:

Specifying a fire-safe valve with genuine API 607 or API 6FA certification is a

fundamental responsibility in process safety management. It moves your specification from assumed performance to proven resilience. By understanding the test, the technology behind the seal, and demanding proper documentation, you make an informed choice that safeguards your operations, your people, and your community.